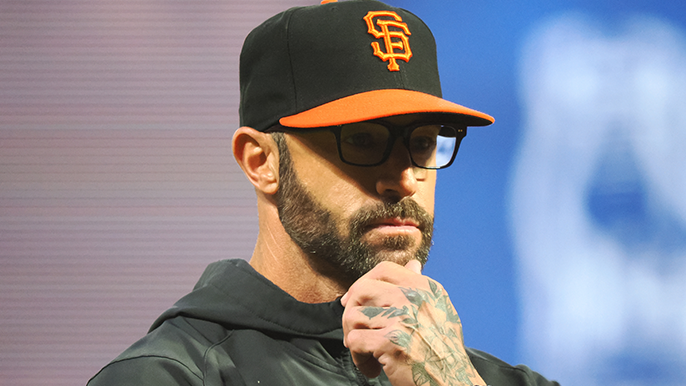

The gut feeling came when Gabe Kapler stood during the national anthem on May 25, one day after the shooting at Robb Elementary School.

“My brain said drop to a knee; my body didn’t listen,” Kapler wrote in his blog. “I wanted to walk back inside; instead I froze. I felt like a coward.”

At that moment in time, Kapler knew he needed to speak up. As manager of the Giants, a leader in the community and an American, Kapler chose to use his platform for good.

Since then, Kapler has skipped the national anthem pregame — save for Memorial Day — in a protest for gun control. Unlike the painstakingly calculated decisions he makes for his day job, Kapler didn’t really do the math when he decided to take a stand. There wasn’t a cost-benefit analysis. With 19 children and two teachers dead in Uvalde, Texas, he had the urge to do what he felt was right.

“Part of being patriotic and American is saying ‘I’m dissatisfied with us as a group,’” Kapler told KNBR. “Us as a group including myself and others in the country. In many cases, a lot of the pageantry turns patriotism into a pledge to blindly follow.”

Friday marked four weeks since the 2021 National League Manager of the Year began his protest of gun violence by not standing on the field for the national anthem. In those four weeks, the carnage has only continued, but the first gun safety law in nearly three decades is expected to be signed into law.

Kapler has said his protest will continue on a day-to-day basis, until he feels better about the “direction of our country.” Although his stance hasn’t quite pierced the national psyche as significantly other gestures have, it has served as a reminder of both the power and limits of a protest in sports.

Activism — from athletes, comedians or other public figures — like Kapler’s can be valuable in elevating conversations. But it’s just one tool in a chest that leads to change. Generally, there are no individual changemakers.

“Athletes aren’t going to change the world by speaking out,” politics and sports writer Dave Zirin said. “But what they can do is amplify people who are speaking out on a grassroots level and draw attention to pre-existing movements. The absence of a national groundswell, even after Uvalde, to have serious gun reform means that Kapler’s protest is going to go more unheard than, say, (Colin) Kaepernick’s protest, which took place in the context of very, very intense movements on the streets of the country.”

In the days following Kapler’s announcement, he received a bombardment of reactionary messages. Some contained homophobic slurs and other elementary insults. Direct messages, handwritten mail, texts.

One combat veteran wrote to commend Kapler’s protest as heroic. A San Francisco-area father whose wife has recurring nightmares about a school shooting with their child starting elementary school thanked the manager. Another called Kapler a “pussy ass motherfucker.” There are hundreds more — hatred, support, pride.

The outrage comes from a small, vocal minority. But what if those same messages sent to Kapler ended up on the desk of Charles Johnson — the Giants’ owner who has supported GOP causes and campaigns? What if angry fans vowed to stop buying Giants tickets due to Kapler’s ideology? The manager must have considered that risk when deciding to take a stand.

The feedback Kapler generated represents a snapshot into America, one that has endured a pandemic, mass shooting tragedies and an attempted insurrection. Pew Research shows Congress has never been more polarized.

Since Uvalde, there have been at least 67 mass shootings — defined as shootings in which at least four people are shot or killed — in America, per The Gun Violence Archive. While those instances often garner more attention, they make up a small percentage of overall gun deaths; there have been nearly 4,000 recorded gun violence deaths since the Robb Elementary shooting.

Guns are the leading cause of death among children in the U.S. There are more guns than people in the country; it’s estimated Americans make up 5% of the world’s population and 45% of gun ownership. There are other contributing factors, but more guns equals more death.

Kapler’s frustration, given the lack of legislative change over the years on gun control, is rational.

This week, Congress passed the first major federal gun safety bill in 26 years. The bipartisan compromise includes expanded background checks for gun buyers under 21, funding for school security, crisis centers and mental health services, but lacks many sweeping items on progressive’s wish lists.

“I respect that at least some members of both parties have come together to pass some legislation to address this issue,” Kapler said via text. “I am not reflexively anti-gun; I have owned a gun myself. But the push by lobbyists and fringe elements to demand no regulations whatsoever on gun ownership has clearly hurt our country, and I think beginning to rein in those extremist tendencies is a step we need to take.”

Whether Congress’s gun safety step is enough in the right direction for Kapler to conclude his protest remains to be seen. The open-endedness of Kapler’s protest — there’s no defined criteria that would make him feel better about America’s “direction” — gives him a built-in opportunity to trek on for other reasons (say, the overturning of Roe v. Wade).

No matter what, he’ll be amplifying what he believes in.

On June 1, Giants president of baseball operations Farhan Zaidi called local reporters together for a Zoom call. Zaidi said both he and the organization support Kapler’s protest.

“The one thing I’m more sure about Gabe Kapler than anything else is he cares,” Zaidi said. “I mean, he cares about the players in the clubhouse, he cares about the people he works with, he cares about this organization, he cares about our fans and he cares about the community.”

Zaidi also encouraged reporters to research the history of the national anthem.

Historians point to the anthem’s presence in sports as a sign of wartime patriotism. The song is about a battle in the War of 1812. Its first documented playing at a sporting event came during the Civil War. It became a mainstay at ballgames during the 1918 World Series that occurred during World War I and was traditionalized during World War II.

People associate “The Star Spangled Banner” with military heroism. Some rival managers weighed in, with White Sox skipper Tony La Russa saying the anthem isn’t an appropriate time for objection. Giants pitcher Alex Wood commends his manager for highlighting injustices, but “it’s not the way I would personally go about doing it.”

“But that’s the great thing about our country,” Wood said. “He feels like he can bring notice to some of the things that are going on in a way that he feels our country is not doing things the way America should be doing them. I completely respect his decision to do that and I understand it.”

As Kapler wrote when he paused his protest for Memorial Day, people have fought and sacrificed in order for Americans to enjoy freedoms — including the unalienable right to peacefully protest. On the holiday, Kapler donated to Everytown and Heart & Armor, empowering people who have dedicated their lives to gun safety and veteran health issues.

The anthem is beside the point. If Kapler remained inside during the anthem without declaring his intentions, would anyone have even thought twice? In 2020, the Dallas Mavericks stopped playing the anthem before games, in solidarity with a player-led social justice movement. Nobody noticed for months.

The general custom within the Giants is more of a casual approach — the players warming up on the field when the song begins, stand. Those in meetings, in the clubhouse or in the batting cage, aren’t required. Rarely does the entire team line up on the foul line.

It’s quite possible members of the Giants, in addition to Kapler, are participating in their own silent protests; many knelt on the foul line in 2020, the summer of racial reckoning.

“I think it could be positive for a lot of people and a lot of people aren’t going to have the same view as him,” outfielder Mike Yastrzemski said. “But it’s really important that he has the space to say what he would like to say. I think that’s the best thing we have going on for us, is that he has that ability.”

Days before he initiated his protest, Kapler sat down with Spike Lee to talk about Colin Kaepernick for the director’s upcoming documentary. Kapler and Kaepernick don’t have a relationship, but it’s easy to see why the manager might admire the former Niners quarterback.

While the parallels between Kapler and Kaepernick are obvious — both sports figures took political stands while representing teams in the Bay Area — the differences are more relevant.

Kaepernick hasn’t played professional football since he protested police brutality and racial injustice in 2016. Kapler, while assuming risks with his protest, likely has no possibility of getting blackballed from his sport. A related, surface level contrast: Kapler is white, Kaepernick is Black.

The impact of any protest is incalculable, but perhaps race is one reason why Kapler’s hasn’t had nearly the cultural influence of Kaepernick’s — or several others.

“These protests, they get attention when there’s a movement,” Zirin said.

Google Trends, a tool that measures interest over time, shows there have been about half as many searches for “Gabe Kapler” during his protest as there was during last October, when the Giants played in the NLDS. There was also more attention on him in 2018, when the Phillies hired him as their manager, and roughly as much as in 2019 when it was revealed he mishandled assault allegations within the Dodgers organization.

A Google search for “Gabe Kapler protest” yields about 194,000 results, much fewer than terms like “Gabe Kapler tattoo” (652,000 hits), “Gabe Kapler contract” (335,000), or “Gabe Kapler diet” (644,000).

Why Kapler’s protest didn’t pierce the national discourse is unclear. Perhaps people are fatigued from an oversaturation of sports protests in recent years. Maybe kneeling for the anthem is simply more visible an act than opting out of it. Maybe Kapler’s pro-gun control stance is so popular, his protest wasn’t controversial enough to make the rounds on talk shows.

The seeming lack of national recognition shouldn’t diminish the significance of Kapler’s stance.

Influenced by his activist dad, Kapler has long studied social justice movements. His ongoing protest puts him in a mosaic of sports activism that includes Jackie Robinson, Muhammed Ali and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. Kapler’s joined coaches like Gregg Popovich and Steve Kerr, who have been outspoken about social justice issues.

He’s done it thoughtfully, purposefully and patriotically.

“He’s part of a tradition now,” Zirin said. “And in that tradition, he’s pretty singular. In terms of who he is, his position on the team. That’s why I think what he’s doing is going to be remembered.”