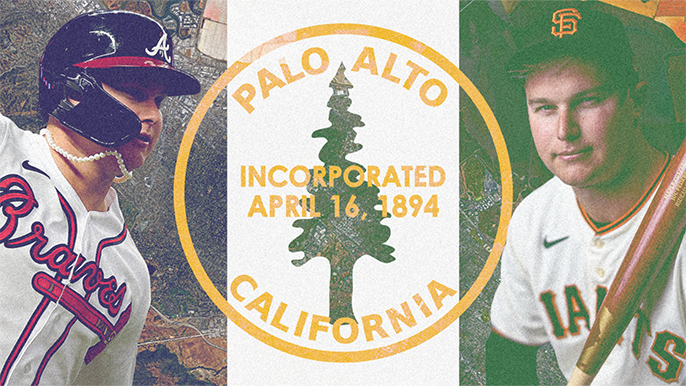

Before he was a World Series-winning, clutch-hitting, pearl-wearing “bad motherfucker,” Joc Pederson was ripping up baseball fields in sunny Palo Alto.

Pederson was a Bay Area kid through and through; a kid who went to the Giants’ 2010 World Series parade on Market Street even after getting drafted by the Dodgers. A kid who got invited into the Giants’ clubhouse during a game and copped some batting gloves from his idol Pablo Sandoval.

Twelve years later, Pederson has his own locker in that Oracle Park clubhouse. The Giants’ big free agent signing is projected to start Opening Day in the outfield, primed to boost a lineup already down two starters.

He’s come a long way to get back to the Bay. As a senior at Palo Alto High School, known locally as “Paly,” Pederson played in front of scouts from all 30 Major League teams about every game. His coach, Erick Raich, chose to lead Pederson off because of his elite speed and so the Vikings could start the game with a man on first when opposing pitchers opted to pitch around the star. Getting him extra at-bats in front of the scouts didn’t hurt, either.

The added attention didn’t prevent Pederson from putting up video game numbers. The center fielder hit .466 with a .577 on-base percentage and .852 slugging his senior year. He was named the 2010 Prep Baseball Player of the Year and got drafted in the 11th round by Los Angeles.

And it seems like everyone who was there where it all began has a Joc Pederson Story.

Raich always wanted Pederson to pitch. A left-hander throwing in the upper 80s in high school? That’ll play.

But of course, Pederson was hesitant. He was coming off a shoulder injury and a prospect of his stature should do everything he can to stay healthy.

Raich couldn’t resist the idea. Even just an inning here and there, possibly closing games. Pederson would be lethal on the mound.

One day, the Vikings’ practice got rained out, so the team was working out at the Palo Alto High basketball gym. Raich challenged Pederson to a game of 1-on-1 in front of the entire team. The terms were clear: if Raich wins, Pederson pitches. If Pederson wins, Raich will forget all about it.

“It was like, ‘alright, let’s do it,’” Raich said.

Pederson, who played point guard before dropping hoops to focus on baseball and football, jumped out to an early lead. Raich, though, wanted to show his team competitiveness and toughness. Raich backed Pederson, 10 years his junior, down and eventually took the lead.

“Then it gets to game point,” Raich said. “And he goes and he throws the ball off the backboard, jumps up and throws the ball down. Slam dunk to win it. I’m like, ‘yup, can’t defend that one.’”

Pederson did eventually pitch one inning when the rest of Palo Alto’s arms were tired. Pederson’s friend since Little League, Wade Hauser, was playing first base when he took the mound.

Said Hauser: “I remember his grandpa coming up to the fence and yelling at me: ‘What is Joc doing? Get his ass off the mound!’ Obviously had his future in mind. I just looked at grandpa and said there’s not much I can do here. Joc had the biggest smile on his face.”

Palo Alto High had an open campus, so during lunch most of the students would cross Embarcadero Road to hang out at Town and Country Village’s open shops and restaurants.

Not Pederson.

Just about every day, Pederson would head to the baseball diamond at lunch time and meet up with his dad, Stu, for batting practice.

“I always just found it funny,” Pederson’s teammate Christoph Bono said. “Here are all the students going off to get lunch, and Joc’s out there with his hat on backwards, tank top on, and he’s just crushing BP.”

Bono, who’s also the son of former 49ers quarterback Steve Bono, remembers scouts catching on to Pederson’s routine. Toward the end of his senior year, there would be up to 20 scouts lined up to watch Pederson hit tanks off his dad.

“It became quite the spectacle,” Bono said.

Pederson starred on Palo Alto’s football team, too, catching 30 balls for 650 yards and nine touchdowns as a senior. He lined up opposite Las Vegas Raiders star Davante Adams and Bono was his quarterback.

One practice, things got pretty heated between Pederson and the defensive back covering him. Bono doesn’t remember exactly what the fight was about, but longtime coach Earl Hansen kicked Pederson off the field. He also suspended his best receiver for the first half of the team’s game on Friday.

Without Pederson, Paly fell down 21-0 in the first half. Bono remembers throwing three interceptions in the first half alone.

But then after halftime, Pederson returned.

“He just came out with a vengeance and was on a tear,” Bono said.

Playing with a purpose, Pederson caught two touchdowns from Bono in the second half and led a furious comeback — though the Vikings eventually fell short.

Even with all the pressure from scouts, the prospect of life-changing money and the necessary sweat equity to succeed, Pederson never had trouble making baseball fun.

“He was never too serious,” Paly teammate TJ Braff said. “Even in big games, he’s still laughing, messing around. He just made it fun, as a teammate, to play with. Made my high school memories a lot of fun.”

The Vikings did a hand-eye coordination drill where hitters swung a paddle-like bat with a hole in the middle and tried to thread a wiffle ball through the gap. Palo Alto’s cages were positioned near the outdoor pool, but angled away from the lanes.

Pederson, though, went rogue on this drill. Instead of angling his stance toward the net, he opened up. Instead of swinging through the wiffle balls, he launched them into the pool to mess with the swim team. Teammate Scott Witte remembers having to run poles with Pederson for that transgression.

He’d make jokes and play tricks like that all the time in practice, Bono recalls. Teammate Will Glazier said before practices on hot days, Pederson would post up on a folding chair atop the team’s dugout and throw water on unsuspecting teammates.

The goofy side also showed up occasionally in games, too.

One game against Wilcox, Pederson sprinted back to track down a deep fly ball. Bono, in right field, got caught admiring Pederson’s jump and forgot to call out “FENCE” as he approached the warning track.

Pederson made the grab but collided full-speed into the fence.

“He kind of just does this falling backwards and just lays out like a snow angel, flat on the ground,” Bono said. “I just remember thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, I just killed Joc Pederson.’ Because I didn’t let him know where the fence was.”

That snow angel pose is something Pederson’s brought to the big leagues.

For any generational talent at the high school level, the home runs are going to stand out.

But Pederson was a little different. As a prospect, he was lean, fast and athletic. He wasn’t necessarily known as a power hitter, though one teammate remembers his dad Stu — a former Dodger — taught him an uppercut swing ahead of the launch angle revolution.

The first home run that sticks out from that year came on the very first pitch of the Vikings’ first preseason exhibition game. Leading off, Pederson crushed the pitch to straight away center field out of Menlo Atherton’s park.

Everyone knew Pederson was talented — he’s the only lefty Bono has ever seen play shortstop, which he did in Little League — but that homer was eye-opening. It set the tone for an incredible season that culminated in a loss in the Central Coast Section championship game.

Later in the season, against rival Wilcox, Pederson put the Vikings ahead with a blast to straight away center field that Wilcox coaches said was the furthest ball they’d ever seen hit.

At Wilcox’s field, there’s a net behind the center field fence to prevent homers from hitting houses. Pederson’s shot cleared the netting and sailed into the neighborhood, Glazier remembers.

“That one was a behemoth,” Glazier said.

The last home run Paly members remember was the last one of the year, in that CCS title game.

The right field fence in San Jose Municipal Stadium — now known as Excite Ballpark — is 320 feet from home plate down the line. Behind the fence, there’s a small parking lot. Behind the parking lot, there’s Solar4America Ice Rink, the Sharks’ training facility.

Pederson’s home run ball went to play some hockey.

“I don’t know if it’s landed yet, but there’s an ice rink in right field and it very well could have landed in it,” Raich said. “It was one of those shots where you don’t see high school guys doing that. And the ball doesn’t even carry to right field there. I think that’s where you kind of go, ‘there’s something different with this player.’ And we lost, but it was still something, I think, that to this day people talk about — that ball he hit out of the stadium.”