SCOTTSDALE — The human became immortal, and the kingpin proved human. Baseball is about stories, and new ones were being born everywhere you looked.

Travis Ishikawa had contemplated retirement not too long ago, and then one swing guaranteed he would never be forgotten. He rounded the bases in jubilation, his walk-off home run at then-AT&T Park securing his place in both Giants and baseball history, sending San Francisco to the World Series.

Brian Sabean’s GM box burst, but so did his eyes on Oct. 16, 2014. The longtime general manager allowed the emotions to overcome him as years of taxing, relentless work was paying off — for the third time in five years.

All around Sabean were jumps and hugs and screams and motion, and the hardened baseball lifer broke down, his head in hands that already were adorned with a World Series ring.

Lee Elder was shown on the TV feed on his left side because being at his right hand might have been a bit on the nose. Sabean’s longtime friend and coworker, nearly a brother, looked over and caught another peek of the human he knew, even if the public so often saw the Giants’ czar differently.

“He didn’t like to let his hair down for a lot of people. He’s a deep, deep thinker, and he’s very guarded,” Elder said. “I think I always felt that was my job, just to make sure he didn’t get ambushed.”

Baseball is about oral and written tradition. Stories that bond players with nothing in common except a game they like to play. Stories that patch together eras like a baseball’s stitches keep cowhide from unraveling. Stories that turn players into myths into statues, which are erected when a legend has enough truth to command that kind of legacy. There was a story on the field, there was another in the box, and there was one of the game’s best storytellers absorbing it all.

That Other Guy in the box’s baseball story is finished at 72 years old, Elder retiring after the 2020 season and leaving a Giants regime in which he was inherited and not handpicked. He helped bring the franchise three titles through both minuscule and colossal moves, and served as a trusted, smiling lieutenant who has never had a bad day and always has a story.

Bruce Bochy, the son of an Army veteran, chuckles hard at Elder’s Vietnam tales. Sabean’s favorites involve George Steinbrenner, which are difficult ones to beat. Just about everyone around baseball and the Giants has heard his Pistol Pete legend.

What Greg Maddux was to pitching, Lee Elder is to stories. Effective to such a degree that it elevates the subject into an art.

“There are some great storytellers in this game,” Giants scout Mike Kendall said. “And then there’s Lee Elder.”

The Giants’ spring training just wrapped up, and it’s the first time Elder has been without baseball since 1988. And yet, he’s not quite a baseball lifer like so many he shared the stands with.

Elder is from Biloxi, Miss., which he’s quick to tell you in a soft voice soaked in syrup. There are “Oh Lawds,” there are “Matter fact”s, there are “o”s that become “a”s — he rolls down windahs — and there are stories that spill into stories that spill into stories.

He loved and played sports growing up, but he wasn’t sure it was going to be his future. He went the junior college route, Mississippi Gulf Coast Junior College, for a year before taking time off to get a job and raise money in hopes of going to the University of Mississippi. And then he was drafted for Vietnam in 1969.

He put in a year of service before he came home and graduated from Southern Mississippi with the GI Bill’s aid. He moved to Ocala, Fla., in 1980 to open up a new Cadillac dealership that was owned by his brother-in-law, which is when he met Steinbrenner, who had a horse farm in the central Florida city.

The legendary Yankees owner would come by often on weekends — his pilot was based in Ocala — and he had pals he could relax with outside of business and baseball. There was Elder, who had both a background in sports and in the service.

“He took a liking to me,” Elder said. “I became, believe it or not, one of the five or six rat-pack guys that ran with him.”

And flew with him. Super Bowls, Final Fours, Penn Relays on The Boss’ jet. To be a great storyteller, you need to have great story subjects.

In the ’80s, Elder and his brother-in-law developed a small advertising company that they sold five or six years later, upon breaking even. He and Steinbrenner had a history by then, and Steinbrenner had heard he was looking for his next job.

“Well, you want to come with the Yankees?” Steinbrenner asked him. “Come to the front office, we’ll have a few yucks, we’ll have a few laughs and you’ll love it.”

Elder’s wife advised him against it because he would no longer be Steinbrenner’s crony, and they knew the stories of how he treated his employees. In the end — which was one day later, because Steinbrenner wanted an answer quickly — Elder agreed to take a job with the promise that if he did not like it, he would quit. He wanted to start at the very bottom, which would ensure his pay would be low and he wouldn’t feel so guilty if he abruptly walked away.

“All right, if that’s how you want it,” Steinbrenner said.

“Where’s the bottom, George?” Elder asked.

“Scouting.”

Elder knew nothing about scouting. But he’d had worse jobs.

“You think I’ll like it?” he asked.

“Like it? You’ll love it,” Steinbrenner said. “When I hire these guys, they’re 14 handicaps. When I fire them, they’re scratch golfers.”

Elder called himself lucky to return from Vietnam. Knowing his way around typewriters would prove helpful. As a clerk typist — he said he could type about 70 words per minute — he mostly stayed on the base and took down messages for his general.

Bochy, whose father served in World War II, frequently queried him about his war stories.

“Well, did you see any action?” Bochy asked. Elder started to laugh.

“I saw a fight in a PX one day,” Elder said of the Post Exchange — a store on base.

“I hid behind my desk every day with a gumbo pot on my head, and only my eyes above the desk because I was afraid someone was going to shoot through that window.”

Elder was sent to Tampa, where the brain trust of the Yankees actually resided; New York was a front. He was told to get in close with a couple executives who would show him how the game was played: George Bradley and Brian Sabean.

“He got a quick baptism,” Sabean said.

It was not lost on the scouts and execs around Tampa that Steinbrenner had just hired a buddy to be around them all the time.

“I think everyone around there thought I was a spy,” Elder said. “George was famous for planting spies. I mean, he even put a spy on [his son] Hank at the horse farm because he thought somebody was stealing steak. So he put a spy not to look at Hank, but to find out who was stealing the meat.”

It wasn’t the baseball work or knowledge that won over Sabean. For a week or two, Elder did little but worry those around him, but he noticed the constant typing of Sabean’s secretary, who needed to input scouting report after scouting report that had been handwritten. Elder could type, and he assisted her while proving he was there for the right reasons.

“So Brian took me under his wing right there,” Elder said.

Sabean soon sent him to scout school in Florida. He would work in the office during the daytime then go to games around Tampa at night to cross-check, to see prospects other scouts already had seen. Elder could try to see what they saw and see what he could glean.

In Elder, Sabean saw a person who was willing to disagree. He had a charm, he had stories, he had a background that set him apart from those around him, and a friendship was born.

“He could be trusted, loyal to a fault,” said Sabean, who at that time was the Yankees’ VP of player development/scouting. “Somebody that would give you a very educated and professional opinion.”

Sabean left to become assistant to the general manager with the Giants in 1993, then rose to GM in 1996. Elder stayed and got his own territory — Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina — while living the grimy scout’s life that is seen more in Hollywood nostalgia than reality in 2021. Maps to guide him from trip to trip; frequently checking the weather where he would be headed because a rain-out could not be salvaged; calling high-school coaches who were gym teachers, then needing to keep feeding the payphone as a secretary hunted the coach down; lugging lawn chairs to the park to ensure there would be a place to sit; staying too many nights at Motel 6s while trading stories with other scouts because it’s easy to be lonely and alone on the road. All while working for the Yankees, the team he adored from his childhood because he could watch them on CBS, with Pee Wee Reese and Dizzy Dean on the call.

The Yankees began winning. Elder earned a World Series ring in 1996. Then ’98. Then ’99. But his friends were leaving. Bradley was gone, as was Sabean. The incoming scouting regime was distrustful of his friendship with Steinbrenner. Hank Steinbrenner was becoming a more prominent figure in the organization, and Elder (twistedly perhaps) preferred the fire of a George or a Sabean.

Sabean called to congratulate him on a third ring in four years.

“I might be ready to move on,” Elder told him.

The Yankees had kept the department under one-year deals, which was Sabean’s way; his view was a scout who didn’t want to be there should leave, and a scout good at his job should not be fearful for that job. The two talked more as the new year approached. Sabean viewed Elder as a brother, a Don Rickles type, a raconteur who could casually ease tensions, and a person who he knew would tell him the truth and not spin answers to please him.

“Jan. 1, 2000, I became a Giant,” Elder said, “and I’ll be damned if that year the Yankees didn’t win a fourth.”

As a kid, Elder was a basketball standout and made the city All-Star team. He remembers in his first seventh-grade game, he scored the winning bucket.

The second game of the season was on the road, and the team had to be at the school at 4 to catch the bus. Elder had the times mixed up and arrived at 5 to find an empty school and bus that had left.

His mother drove him across the city to the game, he got changed in the locker room and sat on the bench in the middle of the first quarter. His coach asked him about the hold-up.

“Coach, Mama was bringing me, and we had a flat tire,” Elder told him. “And [Coach] says, ‘OK,’ and he walked off.”

Elder thought himself a big deal after his debut. So he couldn’t understand why he was now glued to the bench for the entire game.

After the game, his coach approached him in the locker room.

“‘Just so you know, your mother called when you were at the school,’” the coach told Elder.

“Boy, when my dad found out, it was hell to pay. I think at that point, it was: No matter what, I’m never not telling the truth again.”

Elder kept the territories — Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina, where he had plenty of contacts by then — while adding the panhandle of Florida with the Giants. Living in nearby Augusta, Ga., it was doable. What wasn’t doable was Tennessee, which Sabean added to his plate in 2002. The Giants fired one scout and needed Elder to take over in the meantime.

“You gotta be kidding me,” was Elder’s reply.

He didn’t know where to begin, then happened upon Bobby Filotei, a Reds scout whose duties included Tennessee, at a Georgia tournament. Filotei recommended he check out a pitcher from Houston High School, outside Memphis, but the team was playing in Birmingham, Ala., that day.

If he hustled, he could see the pitcher that night. So he got in his car, drove two hours and spoke to Houston coach Lane McCarter — who told him the pitcher didn’t make the trip. He had contracted mono.

“Have you got anybody else?” Elder asked.

“Well, our catcher’s going to Mississippi State. Our first baseman’s going somewhere,” Elder remembers McCarter telling him. “We’ve got a 17-year-old who’s a senior, and he’s got a partial scholarship to Memphis State. He’s not our No. 1 starter, but you can look at him.”

And so that’s how Elder accidentally got a first look at Matt Cain.

It took about three innings for Elder to call Dick Tidrow, the Giants’ farm director.

“You won’t believe it,” Elder began, “but I’m looking at a guy throwing 88 down here, topping out at 89, but he’s got the quickest arm I’ve ever seen on a high-school kid.”

Tidrow told him not to tell anyone, but Cain’s arm started announcing itself to the baseball world. Typically teen arms lose velocity as the season goes on, but the arm speed was real. Elder dragged Tidrow to see him his next start, in which the fastball was 91. Then 92, and it kept rising.

By the time the draft came around, Elder believed he was the only one to have a first-round grade on Cain, who became the 25th-overall pick, who became a three-time All-Star, who became a two-time World Series champion.

Elder played basketball his freshman year at Mississippi Gulf Coast Junior College, which meant that he played on the freshman team; first-years were not allowed on varsity.

“I was a guard, and I was quick,” Elder said. “That was the one thing I could do — I could run. I ran a 10-flat 100 my senior year.”

He also didn’t weigh 130 pounds. The third game of the year came against LSU’s freshman team. Elder picked up the opposing point guard — who he says was 6-foot-4, while Elder’s team’s center was 6-foot-1 — right as he came across half-court.

“I darted right toward the ball, and all of a sudden I’m flat on my face, skipping across the court,” Elder said. “He had went around his back with the ball. When I looked up off the floor, he was dunking it.”

Elder gave his father a call after the 123-77 loss.

“My Lord! They scored 123 points on you?”

“Yeah, they were really good, Pop.”

His father asked how he played, and Elder said OK. He scored eight points, had a couple steals.

“How’d you do defensively?

“Well, my man scored 72,” Elder said.

His father played deaf.

“But Dad, I held him to 29 in the second half!”

Just about everyone around the Giants knows Elder’s Pistol Pete Maravich story.

Elder climbed his way up the ladder with the Giants, moving from the amateur ranks to a major league scout to, eventually, senior adviser to Sabean.

In 2012, he was scouting the NL and looking for help for the Giants ahead of the trade deadline. San Francisco needed another bat, generating little offense from second base while clinging to a slim NL West lead over the Dodgers in late July.

Sabean sent Elder to Arizona to check out a journeyman second baseman playing for the visiting Rockies.

“I want to know if he can hit in the No. 2 hole,” Elder remembers being told.

He saw three games from July 23-25 and came back raving about the 36-year-old infielder.

“We don’t have this guy. He’s exactly what we need,” Elder told Sabean.

So, Sabean asked, he played well?

“He was a below-average fielder, range wise. He has a second-base arm,” Elder said. And he went 1-for-9 with two walks.

He kept talking. He didn’t mention exit velocity because that wasn’t a thing yet; what he did mention was that Marco Scutaro’s outs were hard-hit; that his at-bats were professional; that he wasn’t afraid to hit with two strikes, that his contact skills were excellent. Sabean pulled the trigger.

“If you’d gone off the statistical analysis of that series, you wouldn’t have been interested in Marco Scutaro,” Sabean said. “Lee had that sixth sense, that ability to see there was some luck involved that he didn’t get hits.”

The luck turned when Scutaro became a Giant, led them to the NL West title, became NLCS MVP before driving in the winning run in the clinching Game 4 of the World Series.

In 1994, when Elder was a lowly amateur scout during the season and living in Augusta, looking for things to do in the offseason, he learned a buddy caddied at Augusta National part-time. So Elder went to see about a caddie job days later and timed it right: They were hiring.

“If you promise to show up every day,” the caddie master told him, “I’ll hire you and give you full-time caddie status.”

And so a New York Yankees scout moonlit as a caddie at Augusta National in his offseasons.

Three years later, a last name on the list of that day’s golfers caught Elder’s eye.

“That couldn’t be Bob Lurie, the one who owned the Giants, couldn’t be,” Elder thought. But he was intrigued, and so he latched on to the group as caddie and saw that it was the very same Bob Lurie.

Caddies were not supposed to interact with the golfers; they toted their bags, gave them clubs, were subservient and courteous. So Elder resisted letting his identity get out as he followed around the real estate magnate who had owned the team from 1976-1993.

During the walk from the ninth hole to the Hole 10 tee box, there was a drinks cart, and Elder took Lurie and his friends’ orders, got the drinks and returned.

He was wearing the caddie’s uniform of a white uniform and green hat, but forgot what else he was sporting.

“When I hand him the drink, I had my Yankees ’96 World Series ring on,” Elder remembered. “He looked at it and says, ‘What is that?’”

He explained. Yes, it’s real. He is Lee Elder, whose regular job is scouting for the Yankees. There was a silence.

“How about this, fellas,” Lurie said. “I spent $20 million in 20 years trying to win one of these — and my caddie’s got one!”

The group fell out of the carts laughing.

The rings are a constant source of fascination.

“I think Brady just passed him,” Bochy cracked.

Elder has some second thoughts about the timing of his jetting from the Yankees, and he still feels bitter about not winning more hardware in 2003, when a 100-win Giants team with a superman Barry Bonds lost a tight Division Series to the eventual champion Marlins. Still, who has more rings than his six? After Yogi Berra died in 2015, a representative from the Hall of Fame contacted Elder trying to see if there was anyone living with more rings, and Elder pointed to Whitey Ford’s six. Ford died in 2020, and it’s possible Elder is now all alone at the top.

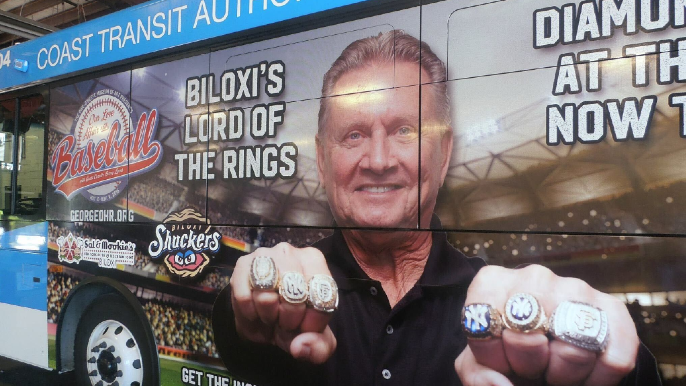

Years prior, Vincent Creel, who works with the City of Biloxi, called Elder and asked if they could display his rings at a showing at the city museum. They wanted to highlight baseball achievements from the area — they would have a Will Clark jersey, too, because he played for Mississippi State — plus several more attractions. Elder asked about their insurance first, but agreed to lend his history to the exhibit. They asked if he could come down for a photo shoot, planning to make his image into a life-size cutout so visitors could see him and his rings.

“Oh, Lawd,” he said upon entering, as the photographer jostled him to put on all six and smile for the camera. He wore the jewelry, he posed, and he forgot about it.

Months later, his wife gave him a call while he was in Chicago.

“She said, ‘I was at the stoplight down at the beach,’” Elder remembered hearing. “‘This transit bus, which goes up and down the beach, taking people all over the coast, is there. I looked out the side of the window and there you are, staring at me.’”

Biloxi was so proud of the cutout they made for the exhibit that they plastered the image against the city’s transit buses for six months. The legendary storyteller acquired a legendary moniker: The Lord of the Rings.

“If you ever said something [pestering] to him,” Bochy laughed, “He’d send that picture to you.”

Lee Elder is a lot of things, including a symbol. He scoffs at some of the statistical worship that goes on in today’s game, even if sometimes it’s applying a new vocabulary and substance to a lot of the insights his eyes taught him.

He loved the passion of George Steinbrenner and Brian Sabean, witnessing his Giants boss flipping plenty of tables when he wasn’t happy with the way the team was playing. He needed to feel as if he were working for a boss — or Boss — who wanted to win and wanted to win now. Sabean needed a shoulder to lean on and an ear to vent to and would call him home from the road during dips in the Giants’ play because he didn’t want to suffer alone.

Others around the Giants sought him out because he had the boss’ attention and respect but not his temperament. You could talk to Elder. You’re better off listening, though.

“You’re by yourself a lot,” Kendall said, speaking for all scouts. “You’re away from your family, you’re in hotel from hotel on 17-, 21-day road trips. You go to the ballpark, and hopefully you see somebody you know, most of the time you do, and you’re able to get through the series with them. But walking into a ballpark and seeing Lee Elder — I think everybody would tell you the same thing: They’re looking forward to five to six games, and you know that you’re going to be comfortable. You know that he’s going to bring the best out of you, as a scout, as a human being. And he’s going to make you laugh.”

Baseball has lost one of the greatest storytellers it has seen. The stories aren’t lost, though, at least not to the people still around. Stories keep baseball going, even when the sport doesn’t quite resemble the game Lee Elder happened upon.

There will always be on-field heroics, telling cutaways and a behind-the-scenes voice who witnesses it all.

“Of course,” Elder said, “Half the stories I couldn’t tell you.”